The work we do impacts our energy. Work nonstop, with little control, in a toxic environment, and we’re on a direct path to burnout.

But what we do after work matters too. If we can recover adequately after work, we can maintain high energy even under demanding conditions.

Today, continuing my ongoing series on energy management, I want to look at our time outside of work: what we do in our time off and how our leisure choices determine the energy we have at work.

Relax or Engage?

One question is whether activities like lounging on the couch and scrolling on your phone or watching television are more restorative than more involved activities like hobbies, sports or personal projects?

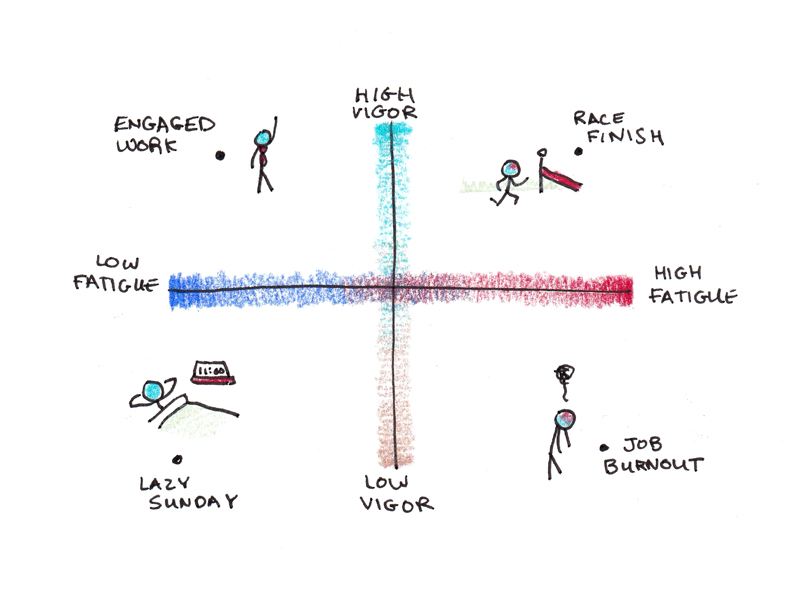

Before we can answer that, though, it helps to make sense of what it even means to “recover” our energy. Researchers describe what I’m referring to as “energy” with two different dimensions: fatigue and vigor.

Fatigue is the feeling of being drained, exhausted and worn down. In this view, the more we work without recovery, the more fatigued we feel. This feeling is amplified when our work is demanding, effortful or stressful.

Vigor, in contrast, is the feeling of being motivated, engaged and driven. We feel vigorous when our psychological needs for autonomy, control and relatedness are met, so our actions feel voluntary and meaningful.

Although there’s a reasonable tension between these two ideas—fatigue tends to be associated with low vigor and vice versa—they’re conceptually distinct. We can be high in both vigor and fatigue, as in the final sprint to finish a race. We can also be low in both vigor and fatigue, as when not wanting to get out of bed to do chores on a lazy Sunday.

Energy recovery can impact our fatigue, vigor or both, depending on exactly what kind of recovery experience we have. Researchers who study the matter split these experiences into four types:

- Detachment. Being able to disconnect from work pressures and stresses after the day ends.

- Relaxation. Calming, stress-reducing activities.

- Mastery. Tackling personally meaningful challenges and pursuits.

- Control. Having the ability to choose what to do with our free time.

Keep in mind, these experiences aren’t a one-to-one match for leisure activities. Rather, think of them as being distinct components of different “recovery experiences.” For instance, we might get detachment and control from watching a movie, but not mastery; or we might get detachment, mastery and control from playing tennis, but not relaxation.

In one meta-analysis, researchers found that detachment and relaxation were more strongly associated with reduced fatigue, and mastery and control were more strongly related to increased vigor.

This suggests that feelings of exhaustion benefit more from detachment and relaxation, whereas feelings of low motivation or drive benefit more from attending to our psychological needs for competence and autonomy.

How to Recover Energy in Your Time Off

This leaves us with the question of which sorts of leisure time activities actually produce detachment, relaxation, mastery or control.

Here, a few reliable findings emerge:

Unsurprisingly, doing chores at home doesn’t do much to recover our energy. So-called “high duty” activities may not be part of our jobs, but they still feel like work and don’t contribute to recovering our energy.

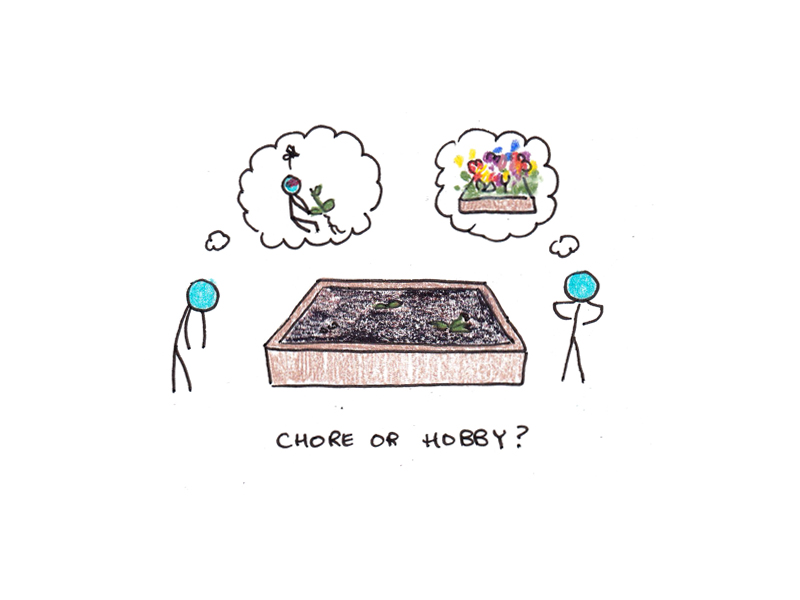

Importantly, the interpretation we attach to these activities matters more than their objective characteristics. Childcare, for instance, can be either a joy or a burden—and thus restorative or draining—depending on whether we enjoy spending time with our kids or feel it as an obligation. Similarly, lots of chores, like gardening, carpentry or home organizing, can also be hobbies.

The critical distinction between “active leisure” and “chore” is whether the pursuit is internally motivated. This, in turn, depends on whether the pursuit feels voluntary, is positively connected to other people, or can provide experiences of competence and mastery.

Another finding from the same literature is that while recovery experiences matter, they’re dwarfed by the impact of sleep. Good sleep has 2-3x the effect of recovery experiences, suggesting that while staying up late to watch an extra episode of television may help us relax, its benefits are undercut by the sleep we lose.

Furthermore, while relaxing with activities like watching television or using a digital device can contribute to reduced fatigue, they’re less likely to help with vigor because we don’t generally find them particularly satisfying or meaningful. This suggests that if we can spend our free time in a way that satisfies our deeper needs, we’ll be more successful at recovering our energy.

Finally, physical activity has a robust effect on energy levels. This owes to some powerful physiological effects of exercise in addition to the psychological benefits of recovery experiences. Mentally engaging but largely sedentary leisure activities, like painting or baking, are often better than completely passive leisure activities. But including at least some physically active leisure activities in our time off is even more powerful.

The Exhaustion Cycle

If you’ve been struggling with low energy, you might have noticed a problem: all of the “better” leisure activities tend to be more effortful!

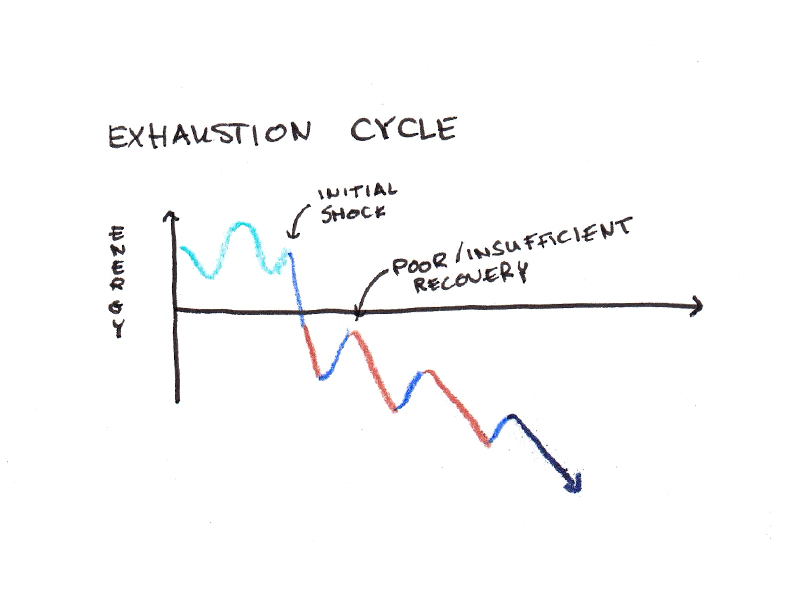

This creates a paradox: when we don’t have energy, we opt for lower-effort leisure activities. But, because those activities don’t really fulfill any of our deeper psychological needs, they aren’t particularly invigorating.

Often this hits as a double whammy: we get overwhelmed or stressed by acute job demands. Because of the added stress at work, recovery becomes more important. But, since we have less time and energy, we cut back on active leisure, physical activity, socializing with friends and the added stress makes our sleep worse. The result is that a short-term stressor can easily become a cycle of exhaustion that can slide into burnout.

This is unfortunate news, as it suggests our energy levels are vulnerable to a draining spiral.

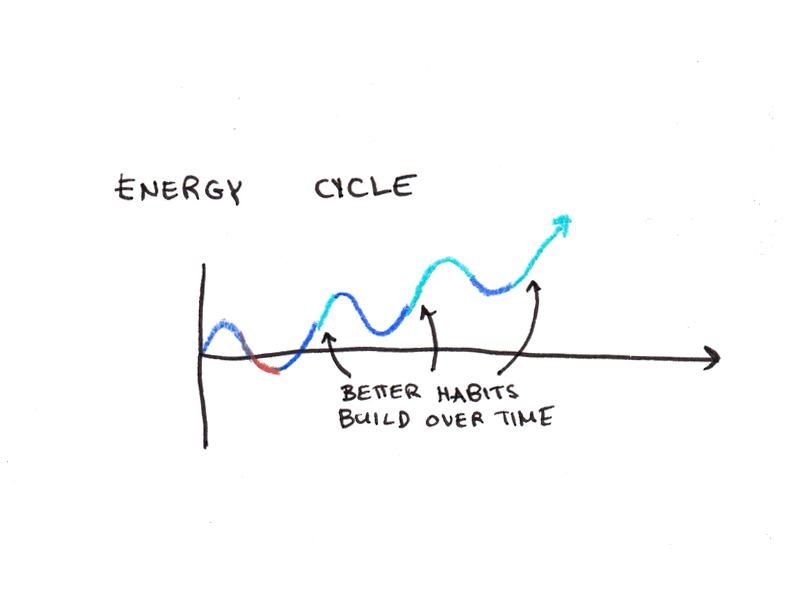

But another way of looking at it is that the spiral of energy also runs in reverse. Just as a sudden wave of work can cause a cascading downward spiral, small positive changes can also compound. Small actions to recover our energy—adding in small bouts of physical activity, taking brief chunks to attend to psychological needs instead of just doomscrolling, putting in a little extra effort to sleep earlier—compound so that we’re able to take on bigger investments in our energy that reap bigger returns.

Instead of a cycle of exhaustion, we can create a cycle of enthusiasm and energy. The key is to take the first steps.

What is your approach to fully recovering your energy after work? What are obstacles do you have to feeling fully energized? Share your thoughts in the comments!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.