I’m fascinated by self-assessment: how we view ourselves versus how we actually are.

As an example, when I ran the first session of my Foundations course, we started with fitness. I was impressed by how many people claimed to already have a solid exercise habit.

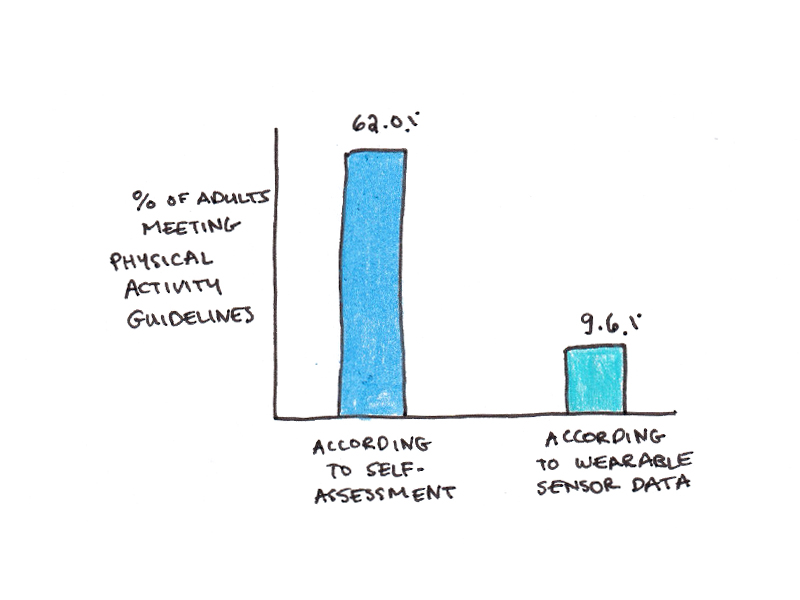

Now, that could be due to sampling bias given the sort of readers I attract (are you all really so fit?). But it could also be because people, in general, overestimate how much exercise they actually do. In surveys most people say they meet recommended exercise guidelines, but the reality is that fewer than ten percent actually do.

Fitness seems to be an area where we have an overly-rosy self-assessment.

Now compare that to the second month in the course, productivity. Instead of optimism, here the median response was about how dismal their productivity was. And, since this is a paid course, many of the students are high-earning knowledge workers who, at least according to the economic definition of productivity, are some of the most productive people on Earth.

Why the disconnect? Why are we so cheerful in our estimation of our exercise, yet so hard on ourselves when it comes to the work we’re doing?

Productivity: Tasks and Priorities

I think part of it has to do with how the entire genre of productivity advice has been sold in the first place: most advice focuses on getting a handle on tasks, whereas most people struggle more with priorities.

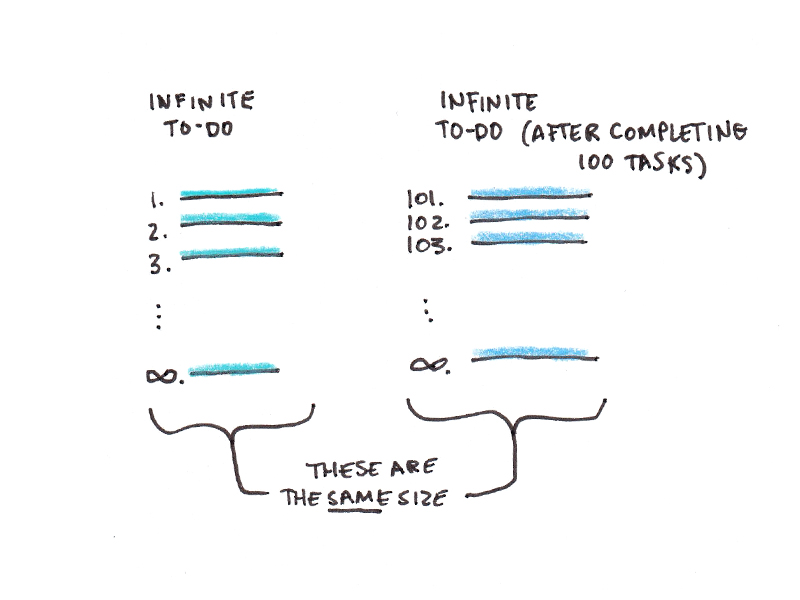

Task-focused advice is about how to get it all done: planners, calendars, to-do lists, batching, Kanban, Pomodoro. There are countless methods designed to make you more efficient and effective at tackling the infinite list of aspirations and responsibilities we all have.

But we can’t get it all done. An infinite to-do list will still have an infinite number of things on it, no matter how many tasks you check off. The high-performing productivity pessimists I encountered in the course were judging themselves by a standard that is impossible to reach.

This puzzle, that the most objectively productive people feel the least productive, was on my mind when I recently reread Stephen Covey’s book, First Things First. I vaguely recalled this book being about weekly reviews and his productivity system. In my memory, it was mostly about scheduling activities on a weekly basis and prioritizing activities that were important but not urgent.

Upon re-reading, I realized that my recollection was mistaken. Most of the book actually argues against the task-focused productivity approach in the first place. The weekly review isn’t mostly about scheduling all your tasks for the week, rather it’s about asking yourself: What sort of life should I be trying to live?

The Compass and the Clock

Of all the late-80s self-help gurus, I like Stephen Covey the best. The folksy stories and aphorisms seem a little hokey today (he doesn’t even use the F-word!). But, compared to a lot of his contemporaries, Covey is wise and thoughtful.

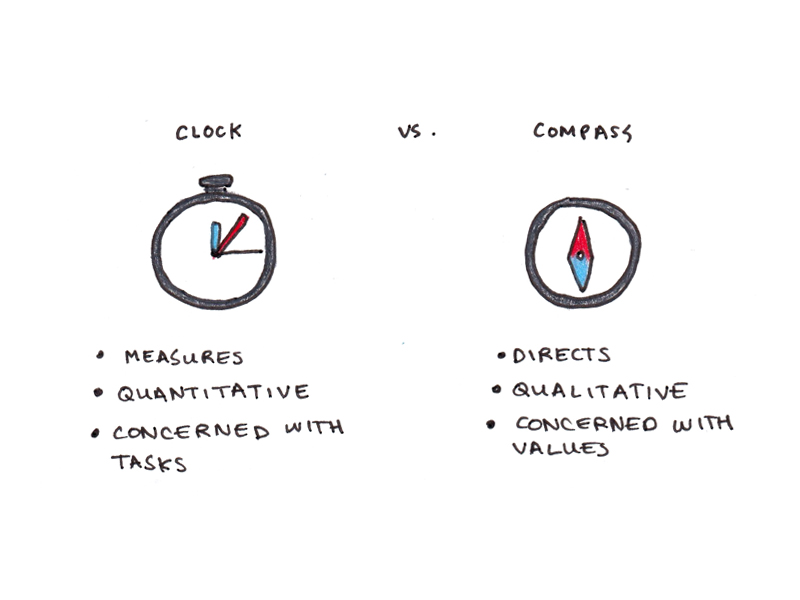

One metaphor Covey relies on is contrasting a clock with a compass. A clock turns time into a measurable quantity that you can slice up, allocate and plan with—something you can manage. In contrast, a compass doesn’t give you a plan; all it can do is show you whether or not you’re headed in the right direction.

The problem of productivity, ultimately, isn’t that we’re not doing everything we would like to (we never are), or that we couldn’t possibly use our time and energy better (we always could). Instead, it’s wanting to feel satisfied with how we use what limited time we have available.

The aim of productivity should not be to worry obsessively about how much we get done. Instead, it should be to feel, at the end of the day, that our time wouldn’t have been better spent doing anything else.

Ultimately, we need to create a vision for our lives and regularly ask ourselves whether we’re actually living up to it. Tasks, projects and purposes will take as long as they need to reach fruition. Our only job is to ask ourselves what really matters and have the conviction to stick with that.

The Weekly Review

I’ve done weekly reviews for much of my life, but they have been largely task oriented: What’s on my schedule? What would I like to get done? What goes on the to-do list for this week? What gets delayed to the future?

That part is helpful. Life rarely goes according to plan, but the plans themselves are still invaluable. However, I now see that this is really only half of the method, and the less-important half at that.

The point of the weekly review is not logistics. It’s purpose is not to schedule every moment of your week in advance or determine exactly which to-do list items you need to accomplish. Instead, it’s an opportunity to take a few minutes to examine what actually matters to you in life, and then ensure that the week that follows is your best effort to live according to how you answer.

I’ll give an example: If I reflect deeply, my kids and family matter more to me than my work. My kids are at an age when childcare can be tricky. This often results in my taking time off or getting less done. In the moment, my first response is often to chastise myself for not being more productive—looking at my to-do list, I definitely get less done than I did when I was single and child-free.

But if I step back, I realize that this isn’t a failure of productivity, instead it’s me being my most productive self. At this stage of my life, I’d rather get less done and have work subordinated to family. A weekly review that reaffirms this for me transforms the frustration of being interrupted with recognition that those very interruptions are my true priority in life.

Here’s another example: I often do a lot of reading and research. Prepping my last book was a multiyear research odyssey. If I compare myself with other authors, it’s clear my desire to drill down into academic research is a bit of a handicap. I could probably sell more books (and write them faster) if I focused on catchy stories and soundbites rather than complicated science.

But, stepping back again, I realize that understanding the world is one of my driving values. Spending “too much time researching” isn’t a mistake given that trying to grapple with the complexity of life is more important to me than producing soothing simplifications.

Building Your Compass

This all sounds good, but what if you aren’t sure what your values are? How do you actually make those difficult decisions to trade-off various parts of your life—and be satisfied with whatever consequences those choices naturally lead to?

Here I part ways a bit with Stephen Covey. He puts a lot of emphasis on having a personal mission statement, but I’ve always found these tend toward either being so generic as to be a platitude (e.g., “I will serve mankind.”) or so specific that they overly constrain your future life (e.g., “I will serve mankind through delivering exceptional quality assurance in the refrigerator repair industry.”).

Instead, I think the truth about values is that you already have them. Even if you can’t put it into words, you already have a deep sense of what’s truly important to you in life compared to what you merely feel pressured to achieve.

What’s needed isn’t to come up with a mission statement you’ve never articulated before, but simply to keep asking yourself why you’re doing things until you have answers that feel self-evident.

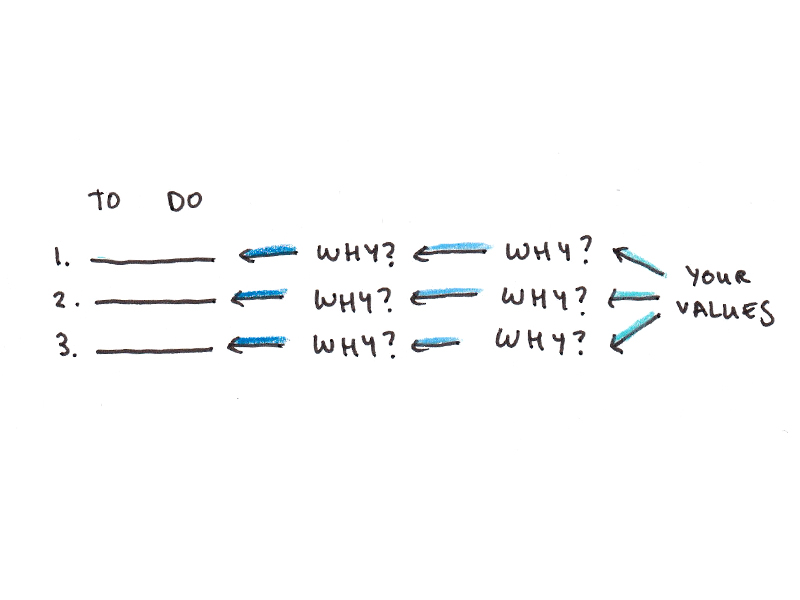

Get a piece of paper and go through your to-do list. Start asking “why” of each of the items on your agenda. Keep asking until you either get to a motivating reason that is intrinsically compelling to you or you realize that there isn’t a good reason for you to be doing it. (In which case, strike it off your to-do list or find a way to get out of doing it at the earliest opportunity.)

This doesn’t have to be limited to inspiring stuff. “Get the leak fixed in my house” may not spark joy in your life, but it’s pretty easy to connect this task to deeper motivations about the material well-being of your home and family. Similarly, a tedious obligation you’re sticking to because you agreed to do it is easy to justify on the basis of being the kind of person who keeps their promises (and perhaps you will think twice before promising something like that in the future).

What this questioning does is identify the things you’re being motivated to do by more superficial reasons and those that truly resonate with you (e.g., “I want a six-pack so people will think I’m hot.” versus “I want to be healthy so I can continue to live well into old age.”). Even more, it also helps you recognize the things that truly matter to you that aren’t “productive” and so don’t normally fit into a task-oriented to-do list, such as building relationships, deep thinking and kindness.

Once you’ve done that, the weekly review is a chance to check in with that vision every week. Not just to plan out when you’ll get it all done (hint: you won’t), but so you make sure you spend your time doing the right things.

If you can do that, you can end the week satisfied with your productivity, no matter how much of your to-do list got checked off.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.