You’re supposed to write an essay, but you procrastinate. The treadmill is collecting dust in your basement. You want to learn a language, start a business or change careers, but those ideas go nowhere. Inaction is something we’ve all experienced.

Inaction, more than anything else, is the cause of our failures and our miseries. If we could consistently do the things we know we ought to, life would be much easier. Your projects would be more successful. Your goals would become a reality. Your life could be better.

We all know action is hard. But why? Why do we struggle so much to take action?

It’s easy to simply take this for granted, to assume laziness is just an intrinsic feature of the human psyche. But it’s also possible to imagine an alternative where action happened without so much inner struggle.

Indeed, you don’t even have to imagine a hypothetical universe to consider this possibility, because there are people who exist in our world who seem to be extraordinarily good at taking action. Arnold Schwarzenegger moving to America, becoming a famous bodybuilder, actor, entrepreneur, then politician. Elon Musk starting PayPal, Tesla, SpaceX and more. Marie Curie winning two Nobel prizes while raising a family as a widowed mother.

There seems to be an amazingly high correlation between the ability to take action and eventual success. Action and success are so closely matched, that it makes the struggles we have with inaction all the more perplexing. If success in life is often as simple as “do things, learn from them, repeat” why do many of us get caught in loops of laziness, self-sabotage and procrastination?

Some Possible Explanations for the Difficulty of Doing

There’s a lot of possible reasons why action is hard. Before I try to offer some explanations, however, I want to look at some theories that don’t do the job very well:

- Talent. Talent, intelligence and serendipity are multipliers of your ability to execute. Obviously, Marie Curie was brilliant. That brilliance, combined with picking just-the-right research project, contributed to her discovering radium and making history. But while talent is obviously an ingredient in success, it doesn’t seem to be all that correlated with taking action. The world is populated by brilliant stars that flame out and mediocre minds that build empires.

- Preferences. I have no desire for Elon Musk’s working life. I’m okay with the fact that this means I probably won’t have a similar level of impact on the world. That’s a difference in preferences, which likely explains part of the range we see in how much people are willing to work hard. But preferences can’t explain why we struggle with ourselves so much. Why procrastinate forever on an essay you know you’ll do eventually? Why start learning the language for weeks if you know you’ll never get to a level where you can use it? Preferences can explain failing to try, but they don’t work well to explain our inner struggles with inaction.

- Capacity for effort. Perhaps effort is simply a different kind of talent, different from intelligence. Have a large capacity and you can easily do a lot of things. Have a low capacity and everything is a struggle. While this explanation does seem partly true, it doesn’t match the pattern of struggle we experience. If your capacity for effort is lower, why wouldn’t this just slow you down, rather than have you experience chronic bursts of activity with inevitable crashes in your goals and projects?

- Motivation. Many of the people who have the hardest time taking action have the most reason to change. Someone leading a grossly unhealthy lifestyle will benefit the most from a small intervention, compared to the hyper-fit trying to lower bodyfat percentage by another 1%. If you define motivation as objectively having a good reason to act, then there’s still a big gap in action that needs explaining. If, instead, you define motivation as a subjective feeling, then we’re simply back to our original puzzle: why do some people feel motivated to do the things they should while others don’t?

My own thinking about the exact causes of inaction aren’t fully developed yet, but I want to try to flesh out some possibilities here, as well as give myself some directions for digging in further.

Possibility #1: Confidence

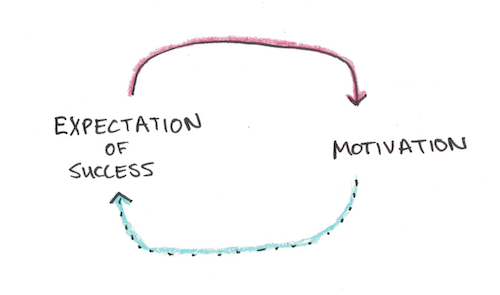

A popular class of theories related to goal-setting are those known as expectancy theories. These are essentially theories that say your motivation to complete a task depends both on the value of the reward you anticipate receiving, as well as your expectation that you’ll actually get that reward.

Your expectations of success, however, also depends on your motivation. This creates a feedback loop where your own expectation of your ability to sustain motivation long-term influences your expectation of success, thus influencing your motivation long-term.

A positive feedback loop can create a system where there are two possible dynamics: an accelerating commitment as you think success is more and more likely, and thus get more and more motivated, as well as a spiral of lowered expectations as you get increasingly discouraged.

Since your expectations of one pursuit often influence future pursuits, this is also something that might stabilize into a general response of doing or inaction in your life. If your projects tend to fail, your expectations are low and motivation withers. If your projects tend to succeed, your expectations go up and motivation stays strong.

Possibility #2: Social-Desirability Bias

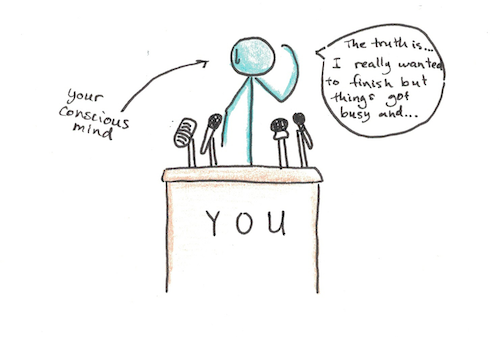

One view of the conscious mind is that it functions more as the brain’s public relations manager than as its CEO, confabulating reasonable-sounding explanations for its behavior rather than actually calling the shots.

If so, this suggests that many of our failures of action are intentional. We fail to take action because the unconscious parts of our mind that drive our behavior have decided not to take action.

Where this gets interesting as a possible explanation, however, is that sometimes inaction isn’t socially acceptable. Thus, we need to feign taking action in order to suggest to others that we do care, even when we don’t. This pretending may even be completely unconscious. The easiest way to lie is to believe you’re telling the truth, so you may even convince yourself you want to pursue a goal when really your unconscious mind is not committed to it.

This might manifest itself in the student who procrastinates on his homework (but doesn’t know why) because he doesn’t really want to study, but has to get the approval and financial support of his parents. Inner friction and anguish may be the price he pays for needing to appear like he’s trying to take action.

Possibility #3: Daydreams Feel Different From Reality

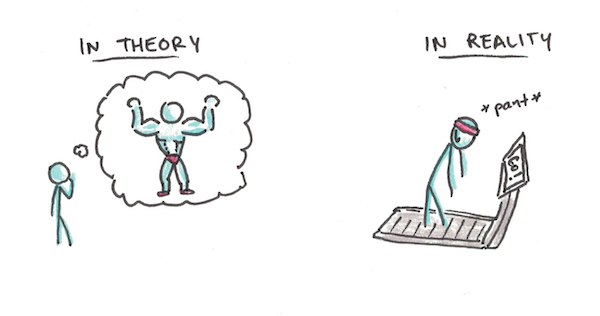

Construal level theory is the idea that we have two characteristic modes of viewing things—an abstract (or far-mode) and a concrete (or near-mode) view.

Many big goals have a far-near incompatibility which can make them hard to take action on. You might think about your fitness goal in terms of losing weight, being healthy and looking great (all abstract, idealized goals). Yet, when you go to the gym you mostly think about how hard you’re breathing, the sweat dripping down your face and how uncomfortable it makes you.

Chronic issues of starting and stopping difficult projects likely depend on this incompatibility of mental states. The person who dreams up the goal is different from the person who executes on it, and coordinating those two versions of yourself may be hard.

Possibility #4: Don’t Stick Your Neck Out

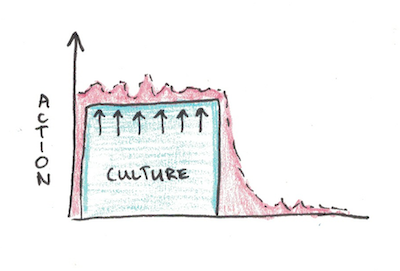

It may be that our hardwiring for ambition itself is based on our environment. Many of our ancestors lived in times when standing out, taking actions that go beyond cultural expectations could get you killed or exiled. Our natures, then, may be trying to sniff out the cost-benefits of taking actions, willing to retreat to placid conformity in case those early ventures get punished.

This might make for a theory of motivation that says, “do whatever your culture requires you to do,” with ventures into different kinds of actions being strongly discouraged if they don’t yield big rewards.

This may also explain why inaction seems to happen with some areas of life (starting your own business), but not others (showing up to work on time). In the second case, there’s a strong cultural expectation that everybody needs to show up on time to work, whereas nobody will blame you for not starting a company.

Our inner struggles may be our unconscious minds trying to find the frontier of action-taking that we’re best suited for, adjusting our ambitions and overall tendency to act based on feedback from the environment.

Possibility #5: We’re Too Short-Sighted

It may also be simply that our modern environment, which is peaceful, stable and allows for long-term accumulation of skills and resources, is quite different from the one we’ve evolved to survive in.

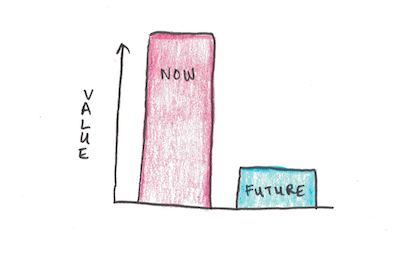

In particular, human beings exhibit inconsistent time preferences for satisfaction here and now, versus long-term rewards in the future. Procrastination may be a delaying tactic to avoid wasting energy here and now, even if you think you might work harder in the not-so-far future.

The ability to accumulate resources likely only started after the Neolithic revolution, where grain agriculture allowed some to save (and steal) and where long-term planning could actually result in evolutionary success.

This may be too short a time-scale to effectively modify our innate psychology, but it may have allowed us to create cultural institutions that counteract our typical short-sightedness. Since, once again, inaction is most prevalent when we’re facing activities without strong cultural pressures, this may suggest that our gap of inaction is due to defaulting to our ancestral, myopic approach to life.

How Can We Get Better at Taking Action?

This subject, why we struggle to take action and how we can improve it, is one that fascinates me. Both because it seems so simple on the surface (“Just do it.”) but so complicated underneath (what do you do when “Just do it” doesn’t work?).

Traditional approaches to this problem have often focused on human will as single thing. But the reality is that our minds are fabulously complicated things, with many different integrating control mechanisms, both conscious and unconscious. To take action, then, you need to not only have new inputs to your conscious mind to nudge you in the right direction, but those nudges need to translate into all the other control systems you possess to keep you headed in that direction.

I have a lot of remaining questions:

- Are there different types of inaction, or do they all have a similar core explanation?

- What separates everyday inaction from the clinical difficulties people who suffer depression or anxiety face?

- Are these simply extreme versions of the slumps and avoidance we all face, or are they separate mechanisms?

- What points in the system are most flexible for adjusting long-term action for the least amount of effort?

As I learn more, I’ll do my best to share it with you.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.