Peter Drucker, the renowned management thinker who first coined the term ‘knowledge worker’ perfectly summarized the problem of focus in work:

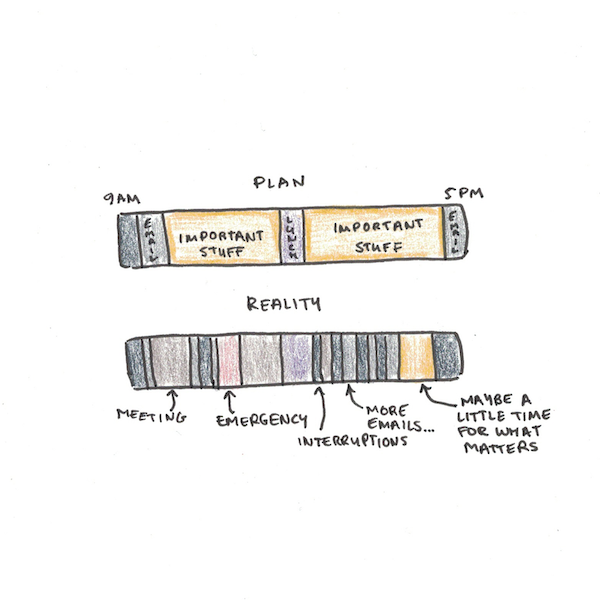

Most discussions of the executive’s task start with the advice to plan one’s work. This sounds eminently plausible. The only thing wrong with it is that it rarely works. The plans always remain on paper, always remain good intentions. They seldom turn into achievement.

Effective executives, in my observation, do not start with their tasks. They start with their time. And they do not start out with planning. They start by finding out where their time actually goes.1

Drucker’s advice to the busy executive is true for us all. We all have good intentions about getting work done. But we rarely stick to them. Instead, distractions eat away at our time, until there is none left.

In my previous lesson, I articulated the need for a philosophy of focus. We need to choose what is worth paying attention to. But this is just the easy part. For without a system for focus, such intentions are just daydreams.

A key element of this system is keeping track of deep work. Knowing where your time goes, as Drucker notes, is an essential first step to taking control over it.

Shallow and Deep Work

Cal Newport, my co-instructor for Life of Focus, first argued for the distinction between shallow and deep work.

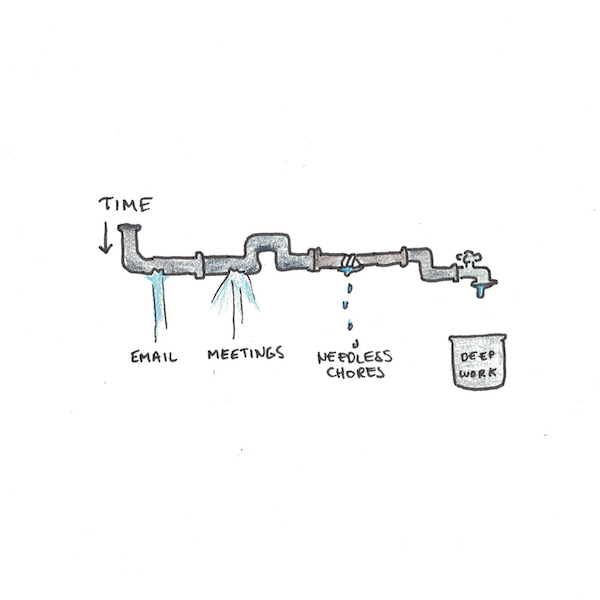

Shallow work is all of the routine activities that accompany work, but don’t particularly require skill or concentration. Answering emails, responding to Slack chats, attending meetings, routine tasks and paperwork.

Deep work, in contrast, is what you’re paid for. It’s the hard-to-do, attention-demanding activity that delivers value. It’s writing essays and crafting code. Planning a new business strategy and conducting research.

Those who can spend long chunks of time engaged in deep work get more done. Not only that, but they end up doing the things which are truly meaningful. Accomplishing your life’s work won’t come from attending a lot of meetings.

The Difficulty of Depth

There are two major difficulties to doing deep work: quantity and quality.

We don’t do enough deep work. Shallow work is usually easier and appears more urgent. Some of this is inflicted from the outside as colleagues and managers add to our to-do list without thinking of the costs. But much of it is self-inflicted. We fail to do the deep work that creates a legacy because it’s easier to toss emails back and forth instead.

We don’t do deep work for long enough. Large, uninterrupted chunks of time are what we need. Drucker himself recognized this fact:

To be effective, every knowledge worker, and especially every executive, therefore needs to be able to dispose of time in fairly large chunks. To have small dribs and drabs at his disposal will not be sufficient even if the total is an impressive number of hours.

Yet, as Drucker observed, plans and intentions aren’t going to work. It’s easy to chastise yourself about not getting enough deep work done. But it’s another thing to consistently do it, week after week.

How to Consistently Perform Your Best Work

The system we recommend in Life of Focus is simple, yet surprisingly effective: always track your deep work hours. Every day, whether you intended to work deeply or not, you should track how many hours were spent concentrating.

Keeping this record can be eye-opening. Like the executives that Drucker advised, you may find that only a quarter of your available working hours are spent on deep tasks.

Even if you do manage to put in enough time, the quality and consistency may be poor. Interruptions may be frequent, or you may find that you have bursts of productivity followed by bouts of shallowness.

In keeping your record, there are three essential features to keep in mind:

- Track in the moment, not in memory. Whenever you set the intention to do deep work, note the starting time. When you get interrupted or stop, note the ending time. Tallies based on your recollection of the day are bound to exaggerate.

- Don’t count tiny chunks. Extended concentration is what we’re after. Small chunks shouldn’t count toward the total. Thirty minutes is a good minimum length, but an hour or ninety minutes is even better as a typical chunk.2

- Add up deep tasks, not just shallow work done without interruption. Deep tasks should require concentration and skill. Each job will have its own, but you should decide in advance which ones count. Don’t inflate your total simply by relabeling shallow work.

Take Action Now

In Life of Focus, we spend the first month working through all the details of getting enough deep work. However, starting a simple habit of tracking your deep work hours can go a long way. Here’s what to do:

- Today, whenever you set the intention to do focused work, write down the time on a piece of paper. When you stop or get interrupted, note the ending time.

- At the end of the day, tally up the total amount of time. Ignore chunks shorter than thirty minutes.

Deep work hours is a simple metric. But encapsulated within it is much of what makes our work meaningful. A working life where you spend your time fully using your mental abilities is one you can be satisfied with at the end of the day. The opportunity to do your life’s work happens each hour of the day. Don’t waste it.

In the next lesson, I’ll shift from depth at work to the focused life at home. A quick reminder that next week, Life of Focus, will reopen for a second session. I hope to see you there!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.