Suppose you have to memorize a lot of material—vocabulary words in a new language, terminology for an anatomy class, legal precedents, or dates of historical events. Which strategy will lead to better performance: mnemonics or flashcards?

In the small and strange world of studying strategies, mnemonics techniques receive a lot of attention:

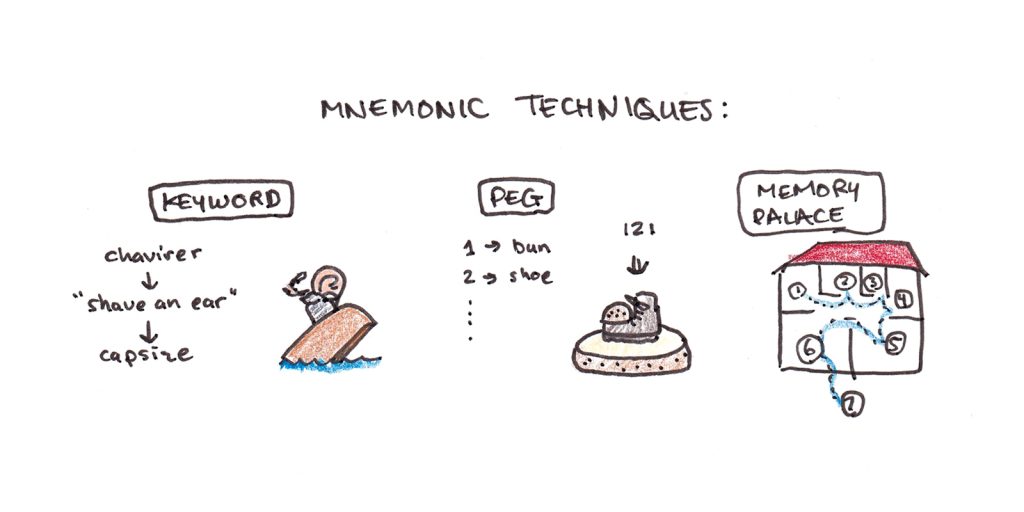

- The keyword method allows you to memorize a word by linking it through an intermediate and fantastical picture. The French word chavirer, which means to capsize, gets transliterated into “shave an ear,” and you picture a bearded ear shaving itself in a canoe that’s tipping over.

- The peg method first links images to numbers (one is “bun,” two is “shoe,” etc..) and then combines these into elaborate visual imagery to encode and recall arbitrary numbers and dates.

- The memory palace uses a mental stroll through a familiar location. You insert fantastical imagery along a pre-remembered linear sequence, allowing you to graft arbitrary information onto this prior structure.

In Moonwalking with Einstein, the writer Joshua Foer explored his dive into elite memory competitions, where people memorize the order of a deck of cards in under a minute, learn the values of pi to thousands of decimal places, or develop perfect recall of unfamiliar texts, verbatim, in only slightly more time than it takes to read them.

Given these impressive results, starting with mnemonics for any skill that depends heavily on memory would seem a no-brainer.

In contrast, flashcards are, well, kinda boring. Everyone has done them before. They’re dry and elementary. You put a question on one side, the answer on the other and you drill (and drill and drill) until you can do them without thinking. No fantastical imagery or secret method. Just repetition.

Flashcards are Underrated

While mnemonics might seem like the obvious choice for learning a ton of new information, research rigorously comparing the efficacy of various studying strategies paints a somewhat different picture.

In their excellent review of ten popular studying techniques, Dunlosky and colleagues summarized the research on both the keyword mnemonic method and practice testing (which includes flashcards). In this review, practice testing got the highest possible rating for usefulness, while the keyword mnemonic got a low grade.

The keyword method does work—that is, students who use it tend to remember the words they were memorizing better than those who didn’t. But it had a number of limitations:

- It takes time to learn and teach mnemonic methods. Unlike flashcards, mnemonics is itself a skill that requires considerable practice to get good at. While this may benefit elite mnemonists, it may not be worth the additional investment for those who simply want to learn Spanish, law or anatomy.

- Mnemonics often take a good deal of time, especially for beginners. It may take a few minutes to create a good link with the keyword method, in which time you could have done several repetitions with flashcards. One study, which equalized the time-on-task between mnemonics and more rote memorization, found that simply increasing repetition provided an advantage over using the mnemonic.

- Mnemonics greatly assist with recall over relatively short intervals, but their benefits might not endure. This makes mnemonics useful in memory competitions—events that require memorization of highly arbitrary information with near-immediate recall. In contrast, much of what we’re trying to memorize needs to stay in our heads for much longer.

Flashcards, in contrast, are simple and quick. While all memory fades eventually, the repetitive overlearning caused by flashcards is one of the more durable ways to create long-term learning.

Direct Retrieval is the End Goal of Learning

Empirically, mnemonics are a bit of a mixed bag. Flashcards seem to have the advantage, at least in carefully controlled studies of longer-term recollection in students who aren’t already trained in mnemonic techniques.

Cognitive theory also lends support to this perspective. A major feature of skill acquisition is that the methods used to achieve a result are not constant. For instance, children learning simple addition start by counting both numbers on their hands, then count from the bigger number and finally retrieve the answer directly.

As expertise develops, more elaborate methods tend to be replaced by direct retrieval of the answer. This is one reason that expertise can be relatively effortless—instead of going through an elaborate process to get to an answer, you just remember it.

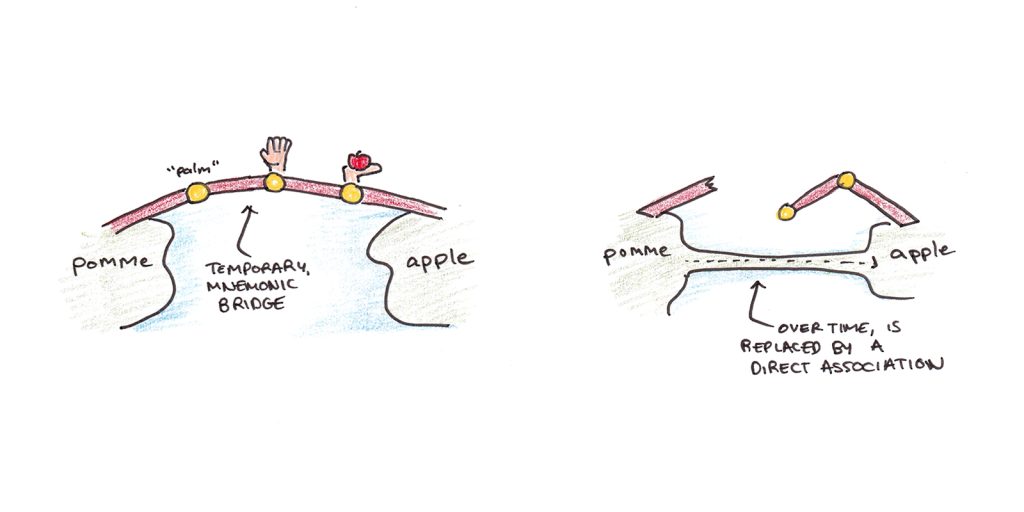

Mnemonics, in this light, can be seen a little bit like the finger-counting. The vivid imagery acts as a bridge between two concepts that would otherwise be difficult to associate. You can quickly learn the mnemonic and it enabling you to cross over from one idea to the other. However, if you practice enough, the two ideas get directly associated—with no intervening imagery.

For situations where fluency is particularly important, such as recalling vocabulary words while speaking, the direct retrieval option is perhaps necessary for a majority of words in order to not get bogged down while speaking too much. This suggests that even if you initially learn a word via mnemonics, direct retrieval will eventually take over as it becomes the faster option.

This suggests that mnemonics are, at best, a temporary measure. They may make learning an association easier, in the short-to-medium term, for words that haven’t been sufficiently overlearned to form a direct association.

Why Not Both?

Of course, flashcards and mnemonics are not mutually exclusive. You can use the keyword mnemonic when you first encounter a flashcard and then study it repeatedly. In this way, the temporary bridge offered by the mnemonic may be beneficial to learning.

This is the approach I’ve used when I’ve had to memorize a lot of material. I start with the keyword mnemonic, when that is relatively easy to do, and follow with a lot of spaced retrieval practice to make the association automatic and robust.

However, I think it’s worth examining the relative efficacy of the two techniques for a few reasons:

- Many people get overly excited about mnemonics and use them instead of flashcards. I think this is often ill-advised for the reasons I’ve articulated above.

- Sometimes the material isn’t mnemonics-friendly. I found the keyword mnemonic great for learning vocabulary in European languages—but far less helpful for Asian languages. The “sounds like” method doesn’t easily discriminate between words in Chinese (which all sound like each other much more than they sound like words in English) so the first leg in the bridge is weak. However flashcards continued to work and were my primary tool for learning Chinese and Korean vocabulary.

- For those not trained in mnemonics, it’s worth asking how much time should be invested in acquiring the skills needed. While mnemonics have some valid use cases, they are often slow and cumbersome without lots of practice, meaning they are best reserved for situations where they’re likely to be used across many memory-intensive subjects.

In short, if you are proficient with mnemonics, by all means, use them to supplement your flashcards. If you’re not, or your subject makes using them difficult, or you simply aren’t sure which one to prioritize, stick with the flashcards.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.