A recurring theme in my ongoing Foundations project is evolutionary mismatch.

This is the idea that our bodies and behavior were designed for a different sort of environment than we live in today. Since evolution is slow, we haven’t had time to adapt new instincts that safeguard us from novel dangers.

Exercise is an example. For most of history, life was laborious, so exercise purely for the sake of getting in physical activity was unnecessary. The sedentary life that causes us health problems today comes from an attitude that was essentially correct for most of our history: don’t move if you don’t need to; it’s better to conserve your energy.

Another is diet. For most of history, starvation was a much more likely danger than obesity. Overeating, when possible, let us build some fat on our bodies for the likely lean times ahead. Only, in our modern world of abundant food, we can consistently overeat.

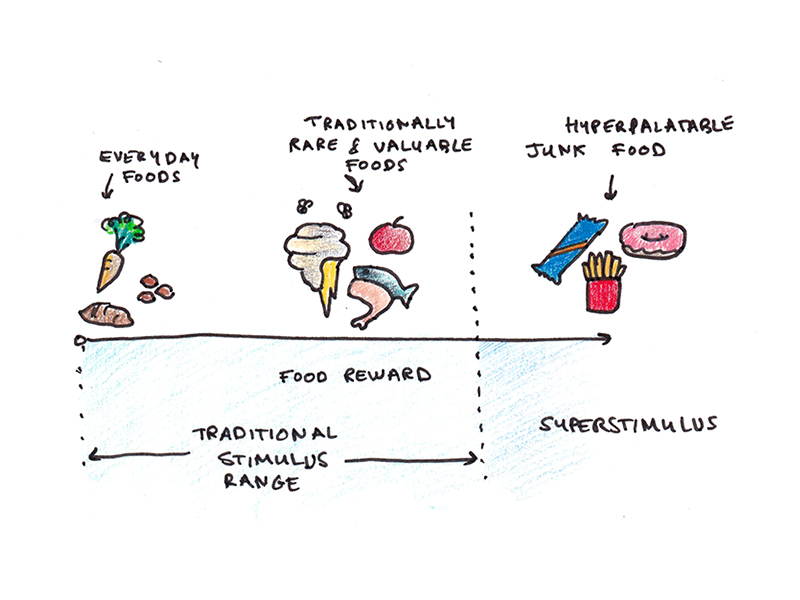

What’s more, modern ultra-processed junk food acts as a superstimulus. That is to say, no food stuff in our ancestral environment has the combination of fats, simple carbohydrates and varied flavors and textures that junk food does. So, what were probably appropriate cues to (modestly) overeat honey, ripe fruit or wild game when they were available has cascaded into a much stronger drive to overeat always-abundant junk food.

For the vast majority of us, modernity has solved starvation, but given us a new self-control problem—trying to eat a healthy diet in a world saturated with junk food.

Attentional Junk Food

While the evolutionary mismatch is pretty widely accepted in explaining our inadequate exercise and nutritional woes, it’s becoming increasingly clear that it also explains a lot of our attentional consumption behaviors.

At work, Gloria Mark’s research suggests we experience interruptions roughly every three minutes and five seconds—roughly half of which are self-initiated distractions. After an interruption, it can take as long as twenty-five minutes to resume the interrupted task. This suggests a repeating carousel of attention—quick dips into different tasks, but rarely sustaining the focus needed for creative accomplishment.

Our personal lives fare no better. We now carry with us devices that have infinite, bite-sized content, algorithmically designed to maximally satisfy our drive for new information. No wonder that Americans report reading fewer books—who can sit through an entire book when even a five minute YouTube video feels too long?

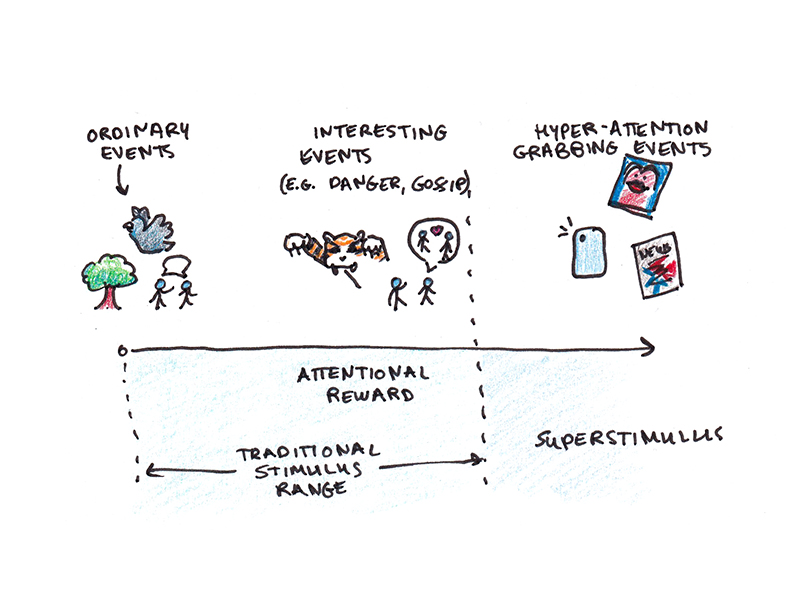

The attentional junk food hypothesis is that these new forms of digital media and work environments are another kind of superstimuli. They exaggerate features that would have encouraged us to pay attention in our ancestral environment, while also divorcing those signals from the actual value they used to reliably provide.

For instance, our brains were designed to pay attention to gossip. Knowing what was going on socially in one’s tribe could be a matter of life or exile. But now we have celebrity gossip, which feeds us information on people we will never interact with and whose status and problems are out of proportion with those of our own friends and family.

Similarly, we’re predisposed to pay attention to potential threats. So online media surfaces rage-inducing examples that exactly trigger our primal threat or fear responses, even if the objective risk is small and the examples rare.

Is a Healthier Attentional Diet Possible?

Given our mismatched drives, what should we do if we want to live a better life?

One answer would be a pessimistic take: there’s nothing we can do. We’ll simply be compelled to eat too much, exercise too little and spend our limited attention on pursuits that don’t matter much to us.

Certainly there’s reason to fear the pessimistic conclusion. Despite decades of well-researched health advice, almost nobody actually follows the guidelines.1 This is even more true when you use objective indicators like heart rate monitors rather than self-reported measures.2

At the very least, we can probably reject the overly optimistic conclusion that simply recognizing this problem is enough to solve it with reason and a bit of willpower. Self-control, while necessary, can never be a permanent solution to problems of mismatched drives—eventually you’ll wear out and give in.

However, I think there’s a middle ground between impotency and ease. We may not be able to rely on willpower to consistently resist our mismatched drives, but we can take steps to redesign parts of our environment to support the kind of life we want to lead.

For me, that meant getting off social media, switching to curated consumption (rather than algorithmic feeds) for most of the online media I did want to consume, and getting rid of distracting apps on my phone and replacing them with Kindle and other long-form content I want to consume.

The end result was much better for sustaining good habits than simply admonishing myself to “do better” when I caught myself wasting hours of the day or getting enraged at the latest social media dust up.

A New Session of Life of Focus

Life of Focus, a three-month course I co-instruct with Cal Newport, is designed to be a tool to facilitate this transition to a more deliberate approach to your attentional life. We wanted not just to teach ideas and facts, but also to help people create new attentional environments so they could overcome the problem of willpower in sustaining behavior changes. Each month of the course, students work through a guided challenge in work, life or mind that both strengthens the skill of focusing and cultivates the environments that support it.

If you’ve felt like the modern world is too busy, chaotic, stressful or distracting to do meaningful work, I highly recommend joining us for our next session, which will be opening for registration on Monday, July 21st.

Footnotes

- And, no, the problem is not that the health advice is actually bad. While specific advice can change as new science is discovered, the stats are pretty clear that while few people follow the advice, those who do have much better health outcomes.

- For instance, in one study over 60% of people self-reported that they meet recommended exercise guidelines, but when tracked using heart rate monitors that amount fell to less than ten percent.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.