In my recent essays about how AI is shaping learning and the future of work, one conclusion that came up in the many comments was the importance of good taste.

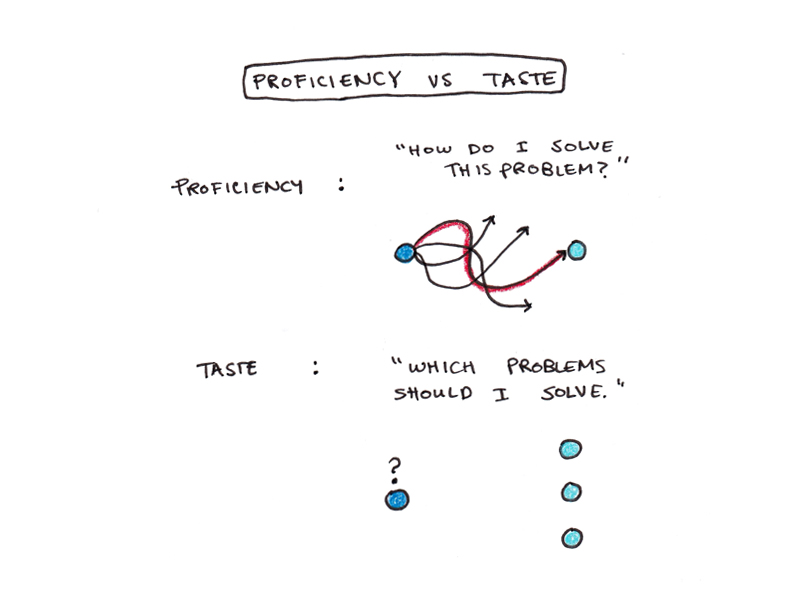

For instance, AI agents can now write a lot of code, but human experts still seem better at deciding what sorts of code ought to be written. AI tools are good at finding solutions, but less useful for figuring out the best problems to solve in the first place.

In other words, current AI may be proficient, but it lacks taste.

But what exactly is taste? And, if taste matters (and may be a remaining bastion of human ingenuity), how do you actually acquire it?

What Exactly Is Taste?

Good taste is hard to define, but easy to understand. Taste is the ability to discern good ideas from bad ones, promising opportunities from dead ends, elegant solutions from the merely functional.

Within cognitive science, there have been two competing perspectives on the nature of taste.1

One school of thought says that taste is simply a subset of general expertise. This was the perspective of the Nobel laureate Herbert Simon. He argued that the way humans find good problems to work on is the same way they learn to play chess or solve logic puzzles.

A different school of thought argued that finding good problems was distinct from solving them. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi was a proponent of this viewpoint. In his book studying art students, co-authored with Jacob Getzels, they found that taste (as I’m calling it) was associated with later artistic success.

I suspect both sides are correct. Taste seems to be acquired like regular proficiency, through practice, observation and feedback, but the two are distinct. It’s possible to have good taste without proficiency (as an insightful critic) or proficiency without taste (as a skilled journeyman dependent on the eye of a master).

The Mental Mechanisms of Discernment

I agree with Simon that taste is a kind of expertise. That means it relies on both intuition and understanding.

Intuition sounds mystical, but it’s mostly just memory in disguise. When we have an intuition that something is good, it’s because we’re pattern-matching it to an example of something good we saw in the past.

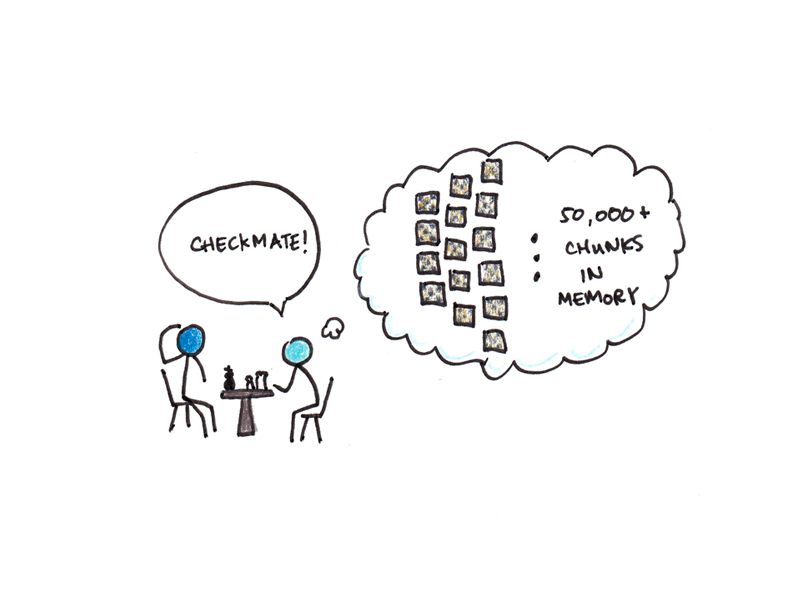

This may sound oversimplified, but compelling work in many fields shows that experts build huge libraries of perceptual “chunks”, with the number of chunks rivaling the number of words you know in your native language, and use these to quickly form an intuitive impression about what to do in a given situation.

Given intuition is largely memory, this component of expertise requires a lot of exposure to acquire. The sheer quantity of pattern knowledge needed for expert performance was a major motivation for the 10,000 hour rule, or the observation that it generally takes even the greatest creators ten years before they produce their first masterpiece.

Understanding is largely a process of building mental models. These models are mental simulations you generate of a situation so you can figure out an appropriate move. Unlike intuition, understanding is an attention-demanding process, but it can provide more reliable results (at least when you don’t need to consider more than a few different possibilities at once).

Taste seems to involve both intuition (quick judgements about the quality of a work or the potential in a given direction), as well as understanding (effortful simulations to anticipate likely design problems and opportunities).

How Do You Learn Taste?

While some of the same mental mechanisms may underlie both taste and proficiency, there are differences.

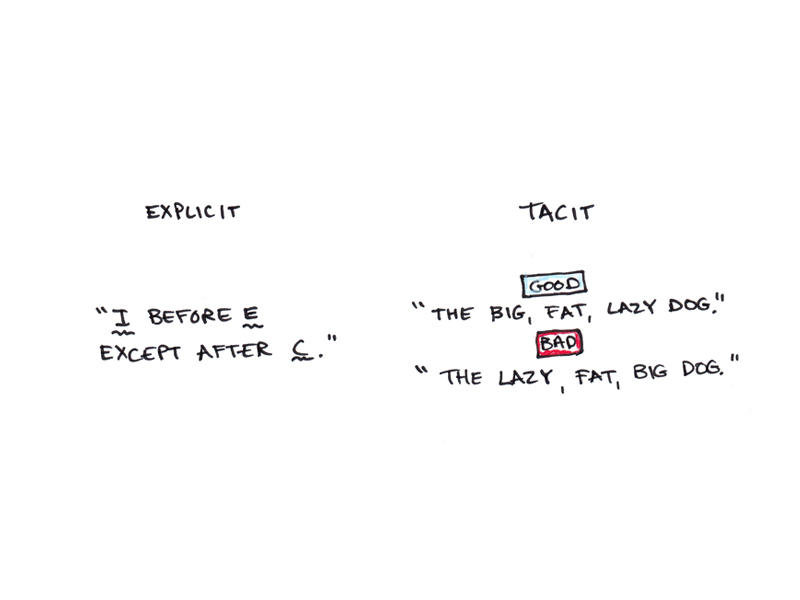

Taste, for instance, is largely tacit. The rules that guide it can’t easily be written down. Those rules that can be articulated usually apply only to a limited set of cases and have so many exceptions as to be unhelpful to a person without an intuitive sense for them.

Proficiency in skills, of course, also depends on tacit knowledge, but the proportion is smaller. Syntax, algorithms and “best practices” are all easy to state, but what makes code elegant or a codebase maintainable is difficult to put into words.

That taste is tacit may help to explain why AI models struggle with it. LLM pretraining is essentially nothing but book learning, ingesting all of the world’s texts, but it omits any expert judgements that could not be expressed with words.

It has sometimes been alleged that the only way to acquire tacit knowledge is through direct experience. After all, if someone can’t tell you what to do, you need to figure it out yourself.

This no doubt plays a role in how experts themselves learn to judge quality. Practice with feedback certainly fine-tunes our sensibilities. (And, interestingly enough, this appears to be the next frontier for AI research, with labs creating countless bespoke environments for agents to learn from practice and feedback, rather than simply feeding in more text.)

However, I suspect that practice and feedback probably play only a supporting role in how people actually acquire taste.

Many people exhibit taste long before they have done much work. I’ve met various writers who had less than a year of experience but quickly began to garner attention and an audience through their writing. While their proficiency improved with practice, it was clearly guided by pre-existing taste.

In other words, their practice efforts were efficient because they already had an extremely strong feedback signal from their own internal sense of quality. They didn’t need audience feedback about what was good or bad to inform them very much. (Which, incidentally, is such a noisy signal that it’s unlikely it plays a major role in how people acquire creative skills.)

Additionally, in spite of the tacit nature of taste, there appears to be a lot of direct transmission of taste from mentor to pupil. Art movements, scientific dynasties and innovation hubs all seem to point to the idea that much of our taste is acquired through guided observation, rather than direct experience. I learn what’s good mostly by seeing good and bad examples. If we had to generate the examples ourselves, few people would produce anything of sufficient quality to bootstrap the learning process.

The role of transmission in taste suggests that even if the rules for taste can’t be written down, they are communicated somehow.

My guess is that the reason taste is difficult to teach through a book is because much of it is communicated through the emotional judgements people make. The students in an elite research lab witness their advisor’s reactions to various experiments, ideas, paradigms and problems. They come to embody those same emotional reactions, even if the basis for those reactions is left unstated.

This makes developing taste more of a process of enculturation than one of training. It is something you acquire through close contact with other people with good taste rather than through only individual observation or direct experience.

Perhaps one possible implication of the rising value of taste over proficiency is a renewed value placed on person-to-person knowledge transmission over book-learning alone. It would be an ironic outcome if the democratization of knowledge on the internet ended up making such knowledge a commodity, with value in careers coming from the kind of esoteric knowledge that can only be communicated face-to-face.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.