A single habit has improved the quality of my book reading more than anything else: reading rebuttals.

To explain, let me first give some context.

I’ve long enjoyed reading big-idea books in science, business or self-improvement. These books range from mega-bestsellers (The Tipping Point; Guns, Germs and Steel) to the relatively obscure (The Enigma of Reason; How Asia Works).

In most cases, I don’t have deep expertise in the topic I’m reading about. The research literature the authors cite is unfamiliar to me. I don’t know whether the proposed idea is a near-consensus opinion or some quirky theory held by a fringe minority.

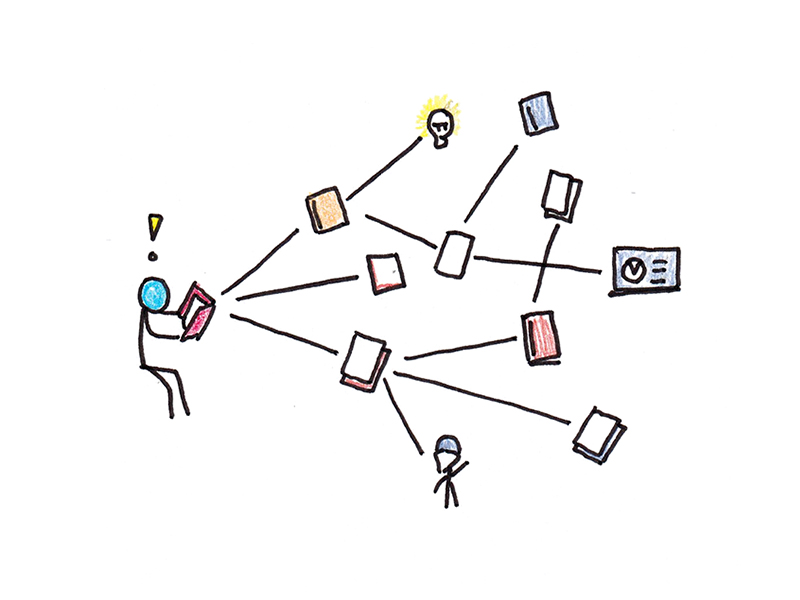

As a result, reading big-idea books can lead to a common pattern:

- You know nothing about a topic, X, and have few or no strong preconceived ideas.

- You read an author with a bold proclamation, Y, which they claim is the right way to think about X. They support this claim with fancy citations, graphs, and impressive rejoinders to objections you hadn’t even considered.

- You leave convinced that Y is the right way to think about X.

- Someone points out some of the flaws in Y. Maybe you read a different book about all the reasons Y is the wrong way to think about X!

- Now you feel hoodwinked. That original author, who proposed Y, had tricked you! What seemed obvious no longer does, and you’re unsure what to believe.

If you’ve been through this cycle a few times, it’s hard not to become cynical. What’s the point of reading books if you frequently end up getting suckered in by bad ideas? How can you learn new things without getting seduced by misleading arguments?

Why “Critical Thinking” Doesn’t Work

The classic advice for dealing with this problem is that we need to become better “critical thinkers.” There are many different versions of this advice, but some of them include:

- We should insist on high-quality evidence. Randomized controlled trials with preregistered designs! Careful econometric methods to distinguish correlation from causation! Large sample sizes! Except such high-quality evidence often doesn’t exist. Even when it does, aggregating it can be difficult—authors frequently cite an excellent study that supports their conclusion, while ignoring equally good research that does not.

- We should point out invalid arguments and logical fallacies. Other critical thinking advocates argue that we should read carefully and note reasoning mistakes. Was that an ad hominem attack? Did the author beg the question in the conclusion? This approach sounds smart, but it assumes all arguments are reached through deduction and laid out as a syllogism. However, most reasoning is inductive (and abductive) rather than deductive. At the same time, many fallacies of logical deduction are still good heuristics for other forms of reasoning (is it ad hominem to accept the word of a credentialed scientist specializing in the topic over a random internet weirdo?), this approach is not a cure-all for wrong thinking.

- We should invest effort to think deeply about ideas and decide for ourselves what to think. In this view, there’s no method at all. Critical thinking is simply being smart about ideas and not letting sloppy ones trick you. Unfortunately, when reading a book, we’ve already set ourselves up to lose—the author has spent years thinking through an argument we’ve never even considered before. They’ve planned their rhetorical moves well in advance, while we must improvise counterarguments while reading.

I don’t believe critical thinking is a skill at all. Instead, most of what we refer to as critical thinking is simply knowing more about the topic being discussed. Experts can spot the fallacies in certain arguments because they’ve steeped themselves in the history of ideas and debates in the field for years. Newcomers have not, and therefore cannot.

But therein lies our difficulty: how do you read a book like an expert without actually being one?

Why Reading “Hostile” Book Reviews is the Key to Smarter Reading

Generating a thoughtful rebuttal to a well-presented idea is hard. It requires a lot of expertise and mental effort, more than most of us are willing or able to expend on a book we bought because it looked interesting.

Instead, the best solution is to seek out the best counterarguments available. These arguments are typically made by competing experts within the same field. What do those experts say is wrong with the book’s idea?

It may sound like reading a rebuttal would simply be an undoing of the original book’s thesis. If you read a book and then then read its rebuttal, wouldn’t you just be left with a confusing mess?

But in practice, it usually doesn’t work this way. Most books you read don’t present a singular thesis; rather, they present an enormous collection of ideas and their implications. When you read rebuttals, they invariably zoom in on a few weak points in the author’s argument.

In fact, reading rebuttals can often bolster your appreciation of the original idea because you come to know which parts are conceded by even its most strident critics. When even your opponents admit that you’re right about something, it’s a strong sign that at least that part of your idea is correct.

More importantly, reading thoughtful rebuttals outsources the expertise and extensive thinking required to find the flaws in big ideas to someone qualified to find them. Invariably, someone who has spent their entire life reading and thinking about a topic will do a better job noticing what’s wrong with an idea than you will.

How to Use This Strategy to Think Better

My preferred source for this type of rebuttal is scholarly book reviews. These tend to be written by experts in the field, whereas journalistic book reviews are often written by a non-expert (although this isn’t always true; be sure to check the byline). To find these scholarly reviews, simply go to Google Scholar and type “Name of Book” and “review” to find some examples.

If this fails, another strategy is to find the book itself on Google Scholar and click “cited by” to find something that discusses the book rather than simply references it. If many authors have cited that particular book, you can search for reviews or critiques within the articles that have cited the original work.

What about books that don’t have reviews? Or the reviews don’t seem to dig deep into the idea itself? In that case, I try to find the academic terms that refer to the sets of ideas the author discusses. Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel looks at geographic or environmental determinism. Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works looks at industrial policy, land reform, and infant industry protection.

Finding the technical terms that refer to the ideas in the book can help you find critiques of those ideas, even if those rebuttals are not aimed at a particular book. Pretty much any idea you can think of has a name, and once you know its name, you can find people who agree and disagree with it.

ChatGPT and LLMs can be useful here. Asking an LLM, “What are the most frequently cited objections to opinion X?” doesn’t guarantee an accurate summary of the literature. But it can give you a starting point by introducing you to some jargon you can search for later.

Doesn’t This Greatly Increase Your Reading Time?

Not really. Most books are a few hundred pages. A book review can be as little as a couple of pages. Even reading a few reviews for a given book shouldn’t add more than 10% to your overall reading time.

Accepting the Imperfection of Most Ideas

One shift that occurs when you regularly engage in this practice is that you realize that there are few arguments without good counterarguments, and few ideas without noticeable flaws. Tyler Cowen’s first law is essentially correct.

But I think accepting that most arguments are imperfect, that even true ideas have persuasive rebuttals, is an essential step to becoming a better thinker. It helps avoid wild swings of fervent belief followed by disillusion and encourages you to see issues from multiple perspectives.

The best habit to improve your reading is to ask after every impassioned argument, “What’s the rebuttal?”

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.