Burnout is miserable. You feel exhausted, but you still need to keep showing up to the job, day after day. Whatever fire you had for your work has now fizzled out—making you wonder whether you should quit and start over.

Why does burnout happen, and how can we avoid it?

Christina Maslach is one of the world’s leading experts on burnout. In the 1980s, Maslach and her colleagues developed one of the first psychological assessments for burnout. In the subsequent four decades, she has built a career investigating the causes of burnout.

Burnout is More than Just Being Tired

Maslach’s research finds that burnout is more than being tired or overworked. Instead, burnout is a combination of three different factors:

- Exhaustion. Extreme fatigue is the first, and most prominent, symptom of burnout. This fatigue is what most people associate with burnout, and it often sets the stage for the other two symptoms.

- Cynicism. Early studies of burnout looked at healthcare workers. To cope with job stress, burned-out doctors and nurses stopped treating patients like people, which was called “depersonalization” in the literature. As burnout research expanded to other jobs, researchers observed that this same phenomenon of emotional distancing and cynicism was associated with burnout regardless of the field studied.

- Ineffectiveness. In addition to being tired and cynical, burned-out workers feel like they can’t do anything about it. Feeling helpless, you might feel like you can’t do much but try to endure.

Exhaustion alone is bad enough, but adding the other two factors can make burnout a pernicious force. Burned-out healthcare workers have been associated with higher mortality rates, and burned-out police officers report more violent force used against civilians.1

What Causes Burnout?

Maslach argues that we’ve adopted an unhealthy perspective regarding burnout in the workplace. Burnout is seen as an individual issue, in which some people simply can’t cope with the stresses and demands of the job.

Maslach illustrates the problem with this approach through the analogy of sending a canary into a coal mine. Colorless, odorless carbon monoxide and other toxic gases can build up deep underground, so miners used to bring canaries, which are particularly sensitive to the effects of these gasses, down into the mines with them. If the canary started to wobble on its perch, workers knew to leave before it was too late.

Treating burnout as a purely individual problem, Maslach argues, is like dealing with dying canaries by trying to find more robust birds who will last longer down in the tunnels—it misses the point entirely. Instead of trying to toughen up the canaries, we ought to be working to fix the elements that make our work environment toxic.

Similarly, Maslach argues against the medicalization of burnout. Some researchers have chosen to treat burnout as a kind of mental illness, like depression or post-traumatic stress disorder. While this may be done with the good intention of getting burned-out workers access to health resources set aside for mental illness, it also perpetuates the idea that the problem is inherent to the workers—rather than the interaction between workers and their environment.

Instead of the individual model, Maslach argues that burnout can be understood as a mismatch between six different elements of the work environment:

1. Workload.

The most obvious condition for burnout is working too much. When workplace demands exceed our resources for coping with them, exhaustion sets in. If left unchecked, this can lead to cynicism and ineffectiveness as we are unable to cope with the demands.

It’s not the occasional burst of intense work that causes problems, but sustained overwork without respite. Organizations that operate in perpetual “crisis mode” or post-downsizing roles where one person is expected to do a job that actually requires multiple people can create chronic conditions of overwork that lead to burnout.

2. Control.

It’s not just how much work you have that matters for burnout, but your ability to take control of it. Maslach found in her research that people with high workloads, who also had a high degree of autonomy for managing that work, were less likely to be burned out.

Instead, those who have a lot of work to do, and little say in how the work is done, are more susceptible to burnout. Being given little flexibility in performing work, especially when the constraints do not seem well-justified, can make an otherwise bearable workload feel unmanageable.

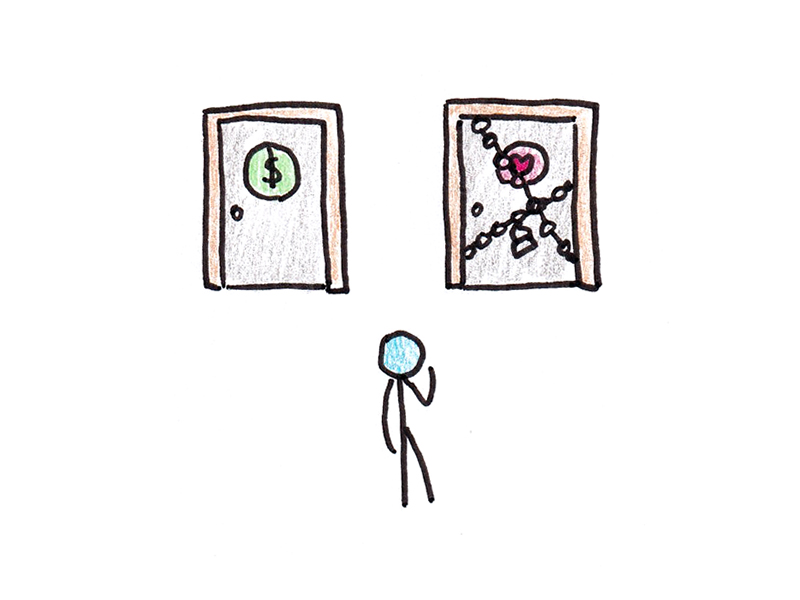

3. Reward.

Too much work for too little pay can exacerbate feelings of burnout. But Maslach argues that rewards go far beyond just getting enough money. (Although that’s important, too!)

Instead, the intrinsic rewards and recognition for a job well done can matter more than the amount written on your paycheck. Showing up to work every day, doing your best, and feeling like nobody cares is a recipe for burnout.

4. Community.

Workplaces aren’t just about efficiency. Our relationships with colleagues and bosses can make a huge difference—both positive and negative—about our feelings for the job. Good friends can make a tedious job bearable. In contrast, bullying and hostility can make a “dream job” miserable.

Burned-out people, in turn, are not much fun to be around. They’re more likely to lash out, be mean, unhelpful or emotionally unavailable. This implies, Maslach contends, that burnout can be contagious. Another reason for treating burnout as an issue beyond the individual is that even if not all employees show signs of extreme burnout, those who do may contribute to a toxic community that worsens working conditions for others involved.

5. Fairness.

When people don’t feel like the rules and rewards of work are fair, it can exacerbate cynicism and accelerate burnout.

Interestingly, Maslach has found that workers care more that the processes are fair than that the outcomes are perfectly equitable. In one case, a company she worked with tried to fix issues of perceived unfairness by giving people more money. However, this approach didn’t work because workers were upset that the rewards were given arbitrarily.

You can probably feel this yourself in workplaces where getting ahead feels like it’s “all politics” or where favoritism and nepotism seem to rule over transparent and fair procedures.

6. Values.

A final mismatch can occur when the values of the person working the job do not correspond to the values expressed in doing the work. A nurse might have gone into healthcare to treat sick patients, but the management mostly cares about increasing revenues. A researcher might have gone into academia with the dream of advancing science, but feels disgusted by constant pressure to churn out grant applications to fund their work.

How to Avoid Burnout

If burnout results from the relationship between work and worker, rather than a purely individual problem, we need to look at both sides of the equation if we want to avoid burnout.

Unfortunately, Maslach notes, this can be difficult. Many organizations insist on treating cases of burnout as problems with those individuals rather than seeing them as warning signs that the workplace is becoming toxic.

That said, there are a few ways we can manage burnout better:

- Take time off. Vacations and sabbaticals are the most commonly suggested ways of dealing with burnout. If the main issue is a demanding workload, temporarily slowing down may be necessary to recover your energy. However, while time off may help with exhaustion, it likely isn’t enough to deal with feelings of cynicism or ineffectiveness about the work.

- Learn new skills. A lack of needed workplace training can exacerbate burnout when you are required to keep up with workplace demands that you lack the skills to meet. Learning skills for doing the work, skills for managing your time and commitments, and social and emotional skills for dealing with stressful situations and people can help you cope better with demanding environments.

- Realize you’re not alone. Workplaces stigmatize burnout, so workers struggling with it are often reluctant to express their feelings. But this can create a situation where burned-out workers are unaware of how many others at their workplace feel similarly, causing workers to feel alone in their burnout even when it is widespread.

Finally, if you don’t feel like you can manage your exhaustion, it may be a good time to quit. If the problem is not just you, but the environment, even the best coping strategies may only go so far. Like the canary in the coal mine, burnout can be a critical signal to get out, not just to toughen up to a toxic environment!

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.