Recently, I shared my predictions about how AI will change the process of learning. In short, I expect that AI will reduce the need for many skills, potentially dumbing down the typical user.

Just as the invention of writing made us worse at remembering things and the invention of the calculator made us worse at mental math, having a technology that can read emails, write code and do homework for us will invariably make most of us less proficient at doing those things ourselves.

But I think the average case here will mask a lot of variation. Many people will learn and think less, but some people will learn much more.

I’ve been experimenting with AI quite a bit in my own research and learning, and the results have been all over the place. For some aspects of learning, AI does a fantastic job, saving me hours of needless effort. But in other cases the results are mediocre, and in some cases they’re downright misleading.

Here are some of my takeaways in using AI as a tool for accelerating learning:

1. Choose which books to read (but you still need to read them).

AI is a great tool for book recommendations. I used it extensively in my recent Foundations project, often using ChatGPT and other tools to recommend books based on fairly specific criteria to round out my reading lists.

But while AI can give some great recommendations about what to read, AI summaries of those books aren’t a good substitute for reading the books themselves. Some of this is a problem of verifiability (more on that in a moment), but it’s a problem with summaries in general—you don’t learn ideas deeply by skimming them. It’s only by reading a book in full that you can truly learn and understand the examples, knowledge base and authorial perspective that allows you to use that information to reason about other things.

AI can help you spot if a book isn’t worth your time so you can read from a tightly curated list that matches your interests, ability level and knowledge gaps.

2. Source alternative suggestions (but do your own thinking).

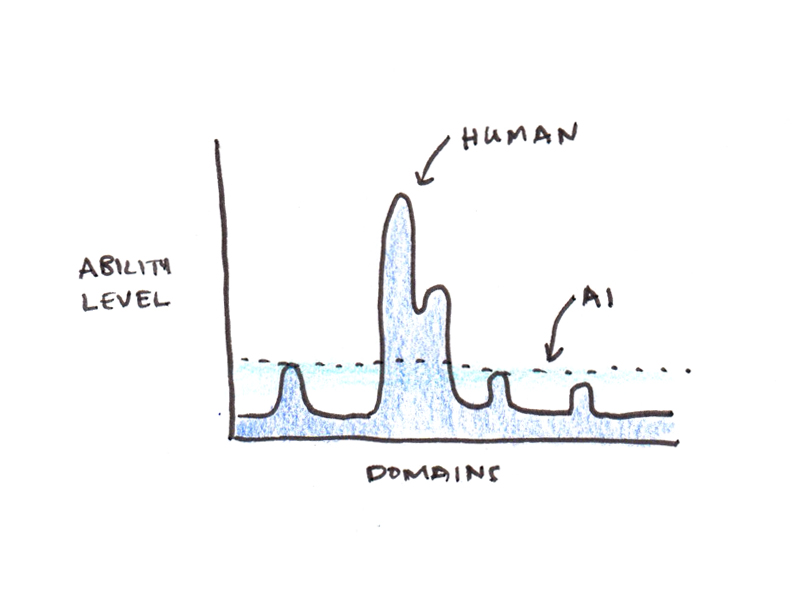

A common refrain in the responses to my recent essays has been that AI seems to be great at things you’re not an expert in, but whenever you are highly competent at a domain, the AI advice seems to be fairly bad. Sort of an AI-version of Gell-Mann amnesia.

For instance, I find AI to be a lousy ghostwriter. Even for little things where I don’t have ethical qualms about using AI, such as generating paragraph-level summaries of lessons I wrote for a course, I’ve found the AI summaries to be inferior and have ended up just writing them myself.

Similarly, I’ve found AI to be unhelpful for giving me business advice, generating flashcards or designing curricula for topics I want to learn. Some of that may be a skill issue on my part, or a lack of good prompts, but the fact that I can generally get satisfactory results in other domains makes me think that the problem is simply that my standards are much higher here.

But even if AI isn’t helpful with the things you know best, its breadth is incredible. Often what AI does best is expose you the breadth of knowledge outside your area of expertise, offering suggestions that you may not have heard before.

When using AI to help me with problem solving, I have found it helpful to ask the AI to suggest alternative ways of approaching the problem that I might not have considered. This often opens solution paths I never would have explored on my own.

3. Ask for verifiable answers when accuracy matters (and fact-check critical information).

Everyone makes a big deal out of AI hallucinations. I agree they’re a problem, but all information sources have factual inaccuracies, so the problem isn’t limited to AI. When I was researching my last book, I was shocked how often even peer-reviewed papers would cite something inaccurately.

I think the actual problem with hallucinations isn’t the error rate, but that the pattern of errors is very unhuman. Generally speaking, when you write something that looks like a well-researched essay, the chance of it having factual mistakes is lower than, say, an off-the-cuff remark on a podcast. AI breaks these conventions because it’s just as likely to hallucinate when it is writing in a seemingly meticulous style as when it appears to be riffing.

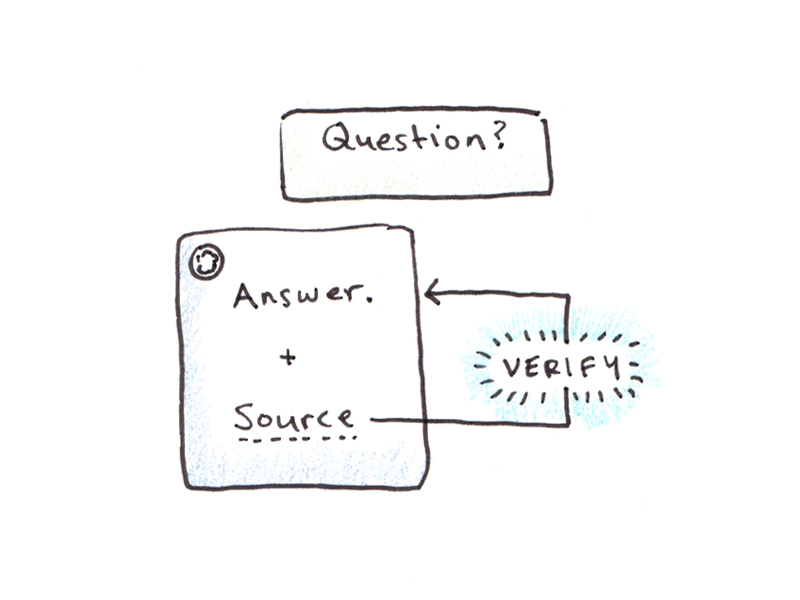

There is a simple fix to this problem: ask questions in a way that they can be verified. Examples:

- Don’t ask for a quote, ask for the source for a quote (so you can check the original).

- Ask for links to the original papers, not just summaries.

- Ask for the code, not just the output of the analysis.

Some other tips include asking the AI to double-check a response (which often kicks off a “reasoning” mode and can catch some hallucinations) and putting the source documents into the chat window and asking the AI for locations in the documents to save you time in verifying the information (Google’s NotebookLM is handy for this).

4. Generate scaffolding first when practicing skills (don’t just ask to “study”).

One of the major weaknesses in my earlier ultralearning projects was a lack of good study materials. Some MIT open classes had abundant problem sets with solutions, others had very few. Some languages had excellent resources, others had almost none. The difference can be night and day in terms of how easy it is to master a new skill.

AI has the power to fix a lot of these problems in finding good practice materials, even as it creates new pitfalls.

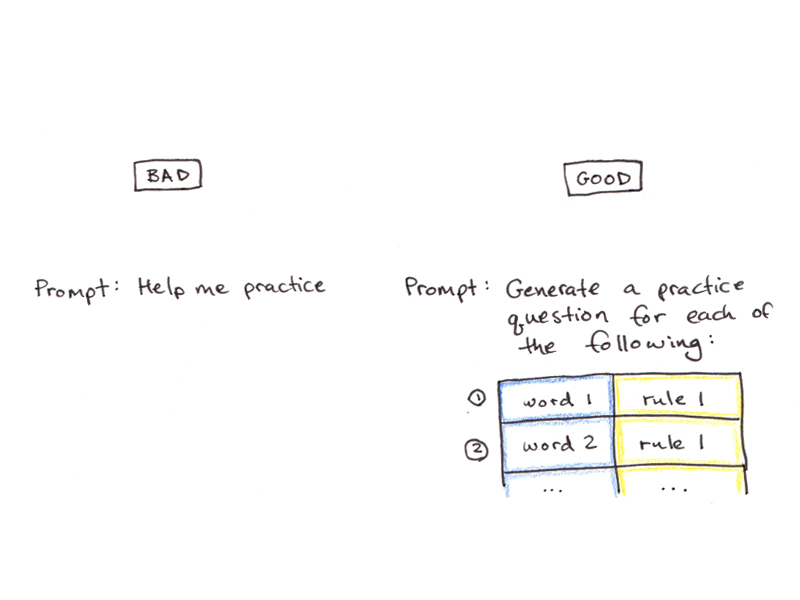

For instance, one of my early efforts in using AI to learn was getting ChatGPT to drill me on Macedonian grammar. That was a genuine help because Macedonian has very few learner resources, and the grammar can be a major sticking point for learning.

Overall, the AI prompts worked pretty well, and I was getting good feedback on things like properly using clitics and conjugating verbs. But after an hour or so of practice the AI would tend to get into “loops”, where the sentence patterns would converge on a handful of variations, and I ended up practicing the same things over and over again.

One solution I’ve found for this problem is to create some scaffolding. In the Macedonian case, coming up with a curriculum, including a list of words, grammar patterns to practice, and various contextual modifiers, and then prompting the AI to give exercises following those different structures helped avoid the “looping” problem.

I haven’t done a math-heavy project since generative AI came out, but my strategy would be similar with technical fields. Don’t just ask the AI to help you study math, but get list of problems of the types you want to learn, and ask it to make variations on the problems. Thus, the AI can help you practice the deeper techniques with a variety of surface-level differences.

5. Use AI as a tutor (not a teacher).

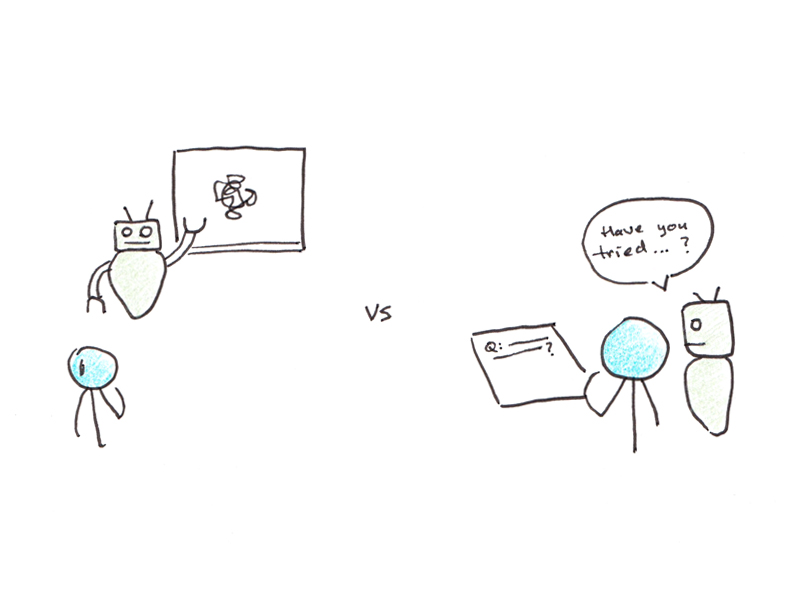

Based on many reader recommendations, I was initially enthused about the idea of using AI to help with curriculum design. This initial step in self-directed learning projects is often one of the hardest—you’re tasked with designing a learning project when you know little about the subject you’re trying to learn.

However, I’ve found that AI is actually really bad at this. The problem isn’t so much that the AI can’t generate a curriculum for a topic, but that it seems to lack a sense for the student’s level and for how to prioritize teaching the relevant concepts.

For instance, I figured a course on the transformer architecture would be right in an LLM’s wheelhouse—it’s usually pretty fluent on AI-related topics, perhaps because of the surplus of online explainers. But the result was a mess. It kept wanting to dive deep into the latest cutting-edge optimizations before explaining basics like the attentional mechanism. Despite hours of fiddling with prompts, I couldn’t get it to produce anything that came close to the median-ranking explanation I could find by searching online.

As a result, I generally avoid “teach me this topic” queries. Those requests, for the moment, seem to be better met by actual people, perhaps because they have a better mental model of instructional sequencing.

However, if you give very pointed questions, the fact that AI can give (generally) useful advice is enormously helpful. I often flit back and forth between ChatGPT and a book I’m reading whenever I get confused or have a question that the author doesn’t answer. AI tutoring seems to work better than AI teaching simply because the way you naturally prompt the AI with specific questions constrains the answer enough that it is more likely to deliver what you want.

Bonus: Vibe Coding an App to Solve Your Problem (But Don’t Reinvent the Wheel)

Most of the time I’m using AI, the simple chat interface works well enough. However, for some learning tasks where you want to repeat the same process again and again, creating an application to do the work for you can be more consistent than repeated prompting.

I’ve made a few helper utilities for learning, such as a tool that takes a Chinese YouTube video as input, transcribes it if subtitles aren’t available, extracts key words and their definitions, and gives a summary in English; another is for helping with painting by breaking down a reference photo into darks/lights/midtones. Most recently, I generated some custom Anki flashcards for Macedonian with text-to-speech audio and sentence variations.

My advice for creating this kind of quick-and-dirty app to solve a personal learning problem is:

- Ask the AI to write the entire thing as one HTML file using JavaScript. While this isn’t best practice for real apps, it means you can simply download the file onto your desktop and run it in a browser.

- While a text prompt alone can work, drawing your interface on a piece of paper and taking a photo of it can help, as can giving concrete examples of similar software/applications.

- If your app idea is fairly complicated, first ask the AI to create specs, and then ask it to build on those specs. Strangely, this seems to work better than just generating the app in one-shot.

- Get an API key so you can query AI within your app. If you’re not sure which one to use or how to do this, ask the AI when you’re building the app. I used this for the Chinese video helper utility, since AI was doing the work behind the scenes of transcribing, translating, identifying key words and summarizing in English.

Even though vibe coding is much faster than coding your own app from scratch (even if you know how), it’s still slow compared to using something off the shelf. Before you start building something, ask your AI if something like what you are looking for already exists. Bespoke solutions are probably best saved for unusual problems or when you have personal idiosyncrasies that aren’t well-represented in the market.

How have you been using AI to assist your learning efforts? Share with me some of the ways you’ve been using AI to learn about new things and deepen your skills in the comments.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.

I'm a Wall Street Journal bestselling author, podcast host, computer programmer and an avid reader. Since 2006, I've published weekly essays on this website to help people like you learn and think better. My work has been featured in The New York Times, BBC, TEDx, Pocket, Business Insider and more. I don't promise I have all the answers, just a place to start.